Tips and tricks for handling a rescue

The quickest overview I could put together. Based primarily on my own experiences, plus reading of others'. Always be open to the possibility that you'll need extra help and support.

Bella came to us as a bit of a refugee from an unpleasant situation.

Many livestock guardian dogs come from such situations; active, ongoing abuse is not uncommon, because of a dreadful mismatch in expectations (“dog will protect anything as soon as it arrives, even as a pup” or “Maremmas don’t need handling”) and reality (“dog is killing livestock and can’t be handled and I won’t tolerate that here”).

Over the years, she’s taught us a lot about handling Maremmas (in particular) that need support.

This article covers a few tips and tricks we’ve learnt along the way.

This article will not help you with dogs needing real help for deep-seated, long-term, fear-driven, aggressive, or other potentially-dangerous behaviours. If you have a dog with these behaviours, please seek professional help.

I’ve provided a list of resources to start, but the best advice is to source specialised trainers in your area who only use positive re-inforcement methods to help re-shape behaviours.

Important: it takes time!!

Re-training Maremmas requires a pretty significant investment of time and effort - mental, physical, and emotional - from you. There are no short-cuts, no magic drugs or food combinations or environments or setups, no memes or snappy catchphrases.

Love on its own is, in fact, not enough.

You can expect a minimum of 1-2 hours’ work a day, every day, every week, every month.

You need to be prepared to:

wake up at odd hours of the night to manage situations

manage your own emotions first

be patient

celebrate improvement in tiny increments over weeks, months, and years.

Because that’s what it takes to change the direction of a rescue Maremma’s life.

Contents

3-3-3

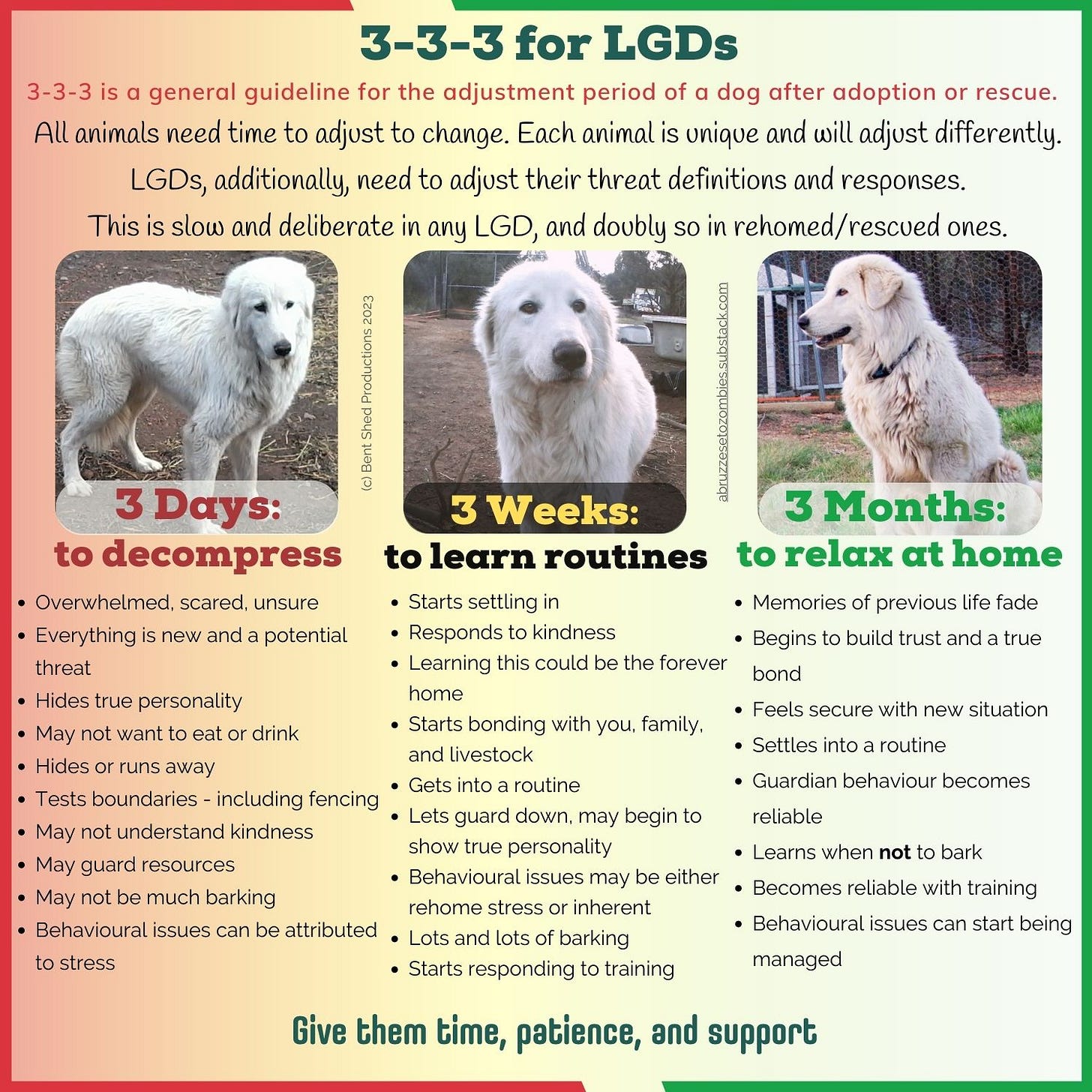

I only came across the 3:3:3 concept in recent years. It is, broadly, a general guideline for the adjustment period of a dog after adoption or rescue.

It applies to any new animal in your household. Heck, it broadly seems applicable to any animal in a new environment - including humans in (say) a new house or job or location.

It applies triply so to dogs that may have some from less-ideal circumstances.

I created an adapted version of this infographic specifically for Maremmas and other LGDs, using photos of my own Bella to illustrate each phase.

Obviously, not every dog in every situation is going to stick strictly to this concept. Some will need longer in each phase; some, much less. Personally I would say Bella easily doubled the time in each stage, because of the abuse in her background; Pieta adjusted considerably more quickly, but took 6 months before she really trusted us.

It’s more about the awareness that there are stages for adjustment to a new situation, and that those stages might take considerably longer than you might have thought, so you need to be patient for much longer than you think.

3-3-3 for LGDs

3-3-3 is a general guideline for the adjustment period of a dog after adoption or rescue.

All animals need time to adjust to change. Each animal is unique and will adjust differently.

LGDs, additionally, need to adjust their threat definitions and responses.

This is slow and deliberate in any LGD, and doubly so in rehomed/rescued ones.

3 Days: to decompress

Overwhelmed, scared, unsure

Everything is new and a potential threat

Hides true personality

May not want to eat or drink

Hides or runs away

Tests boundaries - including fencing

May not understand kindness

May guard resources

May not be much barking

Behavioural issues can be attributed to stress

3 Weeks: to learn routines

Starts settling in

Responds to kindness

Learning this could be the forever home

Starts bonding with you, family, and livestock

Gets into a routine

Lets guard down, may begin to show true personality

Behavioural issues may be either rehome stress or inherent

Lots and lots of barking

Starts responding to training

3 Months: to relax at home

Memories of previous life fade

Begins to build trust and a true bond

Feels secure with new situation

Settles into a routine

Guardian behaviour becomes reliable

Learns when not to bark

Becomes reliable with training

Behavioural issues can start being managed

Tips and tricks

First and foremost: a rescue or rehomed dog primarily wants predictability. Much of their fear and worry comes from never knowing what’s going to happen next, and having to be on constant alert to deal with the next strange thing.

So don’t chop and change quickly. 3-3-3 applies here, too: you need at least three days before a dog will respond to anything new, and a minimum of a week before they internalise it and turn it into “normal”.

Whatever habits you create, get them settled and then try to use them reliably, predictably, and consistently.

Patting. Do NOT pass your hands over their head - this can result in a fearfulcringe. Put them into an upturned "cupping" shape and slowly stroke their jaw, from the front of the lower muzzle and up behind their ears. In fact, all dogs prefer this to the over-the-top pat humans tend to subject then to.

Avoiding the cringe. Don't go over the top of the head - most abused dogs will cringe automatically when you do that, and you just keep re-inforcing the fearful behaviour.

Move calmly and confidently. Don't be hesitant, but don't be violent, either. The same movements you'd use on a newborn baby who needs to be held firmly and gently.

Keep movements low. Sit down as often as you can; try not to loom or stand over them.

Don't put your face in their space.

Avoid unusually loud, soft, or sudden noises. Train your voice to be normal and natural.

Speak constantly; just a constant babble of nonsense, in a cheerful and happy normal tone. It's the tone you need, more than the words. Say their name and warmth and love and affection and humour and joy and glee - all the happy emotions - even if you, personally, are feeling like 14 kinds of horrible.

Bribery. Even Maremmas like tasty cheese and Devon and bacon rinds and cooked chicken, on the whole. Find what they like and shamelessly use it to gently, ever-so-gently, shape new and positive behaviours, such as coming to you when you arrive.

Managing the startle. When they startle at something - as they will - don't change your voice or your movements. THAT'S an absolutely key part of the process - not responding to their fear. They take their cue from you and when you don’t react, they learn that they don’t have to, either.

When you’re startled. If you do react to a sudden situation around your dog - and they happen, of course - use baby-talk-surprise to minimise the dog’s response. “Oh! What a funny noise that was! I quite jumped out of my skin!”. You’ll feel like a fool but who cares? You’re reassuring a dog and, again, it’s the tone of voice you’re after, not the words.

No negativity in your voice. Try not to have conversations with other people at the same time where there's any risk of strong or negative tones coming into your voice. This includes stress, anger, serious upset, and even extreme happiness. To a dog, serious anger and serious joy can sound the same - too loud, too sudden, too extreme.

Be normal. Adjust your behaviour to a certain extent, but don't retreat too far into being tentative, excessively gentle, or reactive to her perceived fears. Dogs need to know that regardless of what's going on in their head, you'll keep being there, and your boundaries will always be the same.

Be positive. Get your OWN head in the right place. You need to be calm, amused, firm-but-gentle, and know the boundaries to be put in place.

Get your own head in the right place

Do NOT let your personal emotions leak on to them. That was the hardest thing I had to learn, as I'm a sort of stressed person and I was having a truly awful year when we got them. But I had to let it go in order to calm a traumatised dog down. When things go backward - and they will - let go of assigning fault. It's happened, now you deal with it with calm and love and the best good-humour you can muster up.

“Fake it till you make it". Force all those good emotions into your voice, like the fakest customer service drone in existence. Make your dogs the repository of joy, so that saying hello to them automatically becomes a joy in itself.

Control yourself. If you are angry or upset, do NOT go to them. Keep away until you've got control of yourself. Your self-control is needed to bring balance back to their life.

Control them. A scared dog still needs to be told "no" at times. They can't be allowed to get away with behaviour that wouldn't be permitted in a non-scared dog.

Accept that if you have to say a very firm "no" to manage potentially risky/dangerous actions - sniffing at snakes, stealing food, jumping/digging fences, running away - you will probably go back about a week in progress.

BUT you can use that fear to your benefit in a tiny way - you want dogs to be a bit fearful and hesitant of certain situations, such as jumping fences or belting through gates before they're properly opened. So if you have to yell a huge and terrified "NOOO!!" when that happens, and make them temporarily terrified ... that is a price you need to accept to keep them safe. But keep that action for truly life-or-death situations, because they’ll never forget the lesson learnt there.

The key to curbing undesirable behaviour is to be calm, unemotional, and utterly consistent.

Greet with joy

Here's a very specific set of actions that helped me enormously.

When you see your dog/s, get down on one knee, open your arms wide, and say their name with glee. Don't bother saying "Come" because you'll just be disappointed, but say "Hello [name], how are you today??" as if seeing them is the high point of your day. (Cos let's fact it, it probably is … ). I often say a delighted “PUUU-PPIESSSS!”.

Have a treat in hand (see "bribery" above) to re-inforce everything.

If the dog doesn't trot over to you immediately - well, that's to be expected. They’re still learning. Sit down comfortably and start telling them about your day, as if you were telling a bedtime story to the kids. Say their name often and look at them, so they know you're vibing at them, but don't move toward them. Put your treats in front of you - make sure they're warm and smelly - and then ignore them.

If they do meander over and sniff the treats, keep chatting. Maybe dangle down a casual hand.

If they eat the treats and then sit nearby, lovely. Say their name, give them a nice single cupped pat under the chin, then keep on chatting. Keep handing over the treats absent-mindedly. You're not training them to anything except the idea that being near you, and accepting you moving around and talking, is the Best Thing Ever For Puppydogs - and that you are giving off the impression that being around them is the Best Thing Ever For Humans.

You can do this while doing your everyday chores, too. Move around while you feed the chooks and water the ducks and scratch the pony. Throw out those treats. Chat to everyone. Move normally. Sit down when you can. This all lays the groundwork for calm, happy normality.

So when you see them next moment and gleefully say their name, they know for a rock-hard certainty that you actually mean it and when they trot over in response, they’ll be treated like royalty. Every time. For the rest of their days and months and years.

Because you absolutely can train and reward a Maremma with nothing more than affection.

And in return, you’ll realise with no little surprise that you have a Maremma with a startlingly good recall.

Provide their own space

There are many, many resources that will help with identifying and handling problematic behaviours; too many for this small article.

But in the first instance, giving a rescue Maremma its own space - lots and lots of its own space - can help enormously. If possible, a room in your house with its own doorway to a larger enclosed outdoor area can provide the perfect mix of solitude and safety for everyone.

What you’re looking for is a location that is:

Secure. Good solid fencing of some kind in the outside area. Use toddler gates for internal doorways. Things that will prevent both the dog getting out, and other things from getting in; things where you control the entry and exist in reliably, calm ways.

Enclosed. A kennel or crate or something else that serves as an open-fronted “den”, to provide a feeling of safety and security.

Central enough that the dog can see and hear the normal activities of the house, yards, and property, but on the outside somewhat so it doesn’t feel surrounded by all the new things.

Large and well-appointed enough for them to stay in for many hours at a time, or even a day or two, if and as need be.

Somewhere they can toilet themselves, so they’re not reliant on you to take them in and out.

Never, ever to be used as a punishment or disciplinary area.

A place where you can easily visit them regularly to provide play, quiet company, brushing, attention, food, water, love, and treats.

A place, in short, that the dog can regard as their safe, happy place.

Note: there may be a risk that the dog starts to resource-guard this location, which is almost the logical extension of feeling safe and happy in their own space.

Be consistent and predictable

I cannot emphasise enough how important consistency is.

Animals - all animals, even humans - don’t deal well with change, the unknown, the unpredictable. Some of us deal better with unexpected situations than others, and some like the challenge - but it’s still a challenge.

A considerable amount of any dog’s fearful behaviour comes from being in an unpredictable, inconsistent environment. They are constantly having to react to different situations, and have no “normal” to relax into. The whole world becomes one huge threat.

And we know how Maremmas are bred to respond to threats - bark and push to make it go away.

Thus, the absolute best thing you can do to relax a rescue is provide calm, consistent, predictable, reliable behaviour. Allow the dog to start learning a concept of “safe normal”, so “threats” can be relegated to their proper “things that aren’t normal” status and managed accordingly.

This doesn’t mean, by the way, that you must provide dinner at 7pm on the dot. In fact, that’s setting yourself up for trouble, as “late” becomes “not-normal” and, thus, a threat.

But allowing rescue dogs to know that they will (for eg) get a meal after sunset, every day, without fail; that’s a reliable routine with flexibility built-in. Getting used to those flexible boundaries makes a dog more resilient, less concerned if something goes a little awry and you can’t feed them until midnight one night.

Other things that help rescues develop a sense of “good normal”:

routines such as going for a leashed walk around boundaries

having a regular brushing session, even if it’s only for a few seconds at a time

always being responded to with kindness if they’re feeling worried or fearful and have expressed that fear or worry through barking, howling, scratching, or other behaviour

consistent responses to certain behaviours, both good and bad:

reliable praise/approval voice for barking at threats like fox sounds

reliable calm chiding for barking or chasing the wrong thing like the family cat or a hen’s new-hatched chicks

reliably being walked away from situations if wrong behaviour is exhibited around them (stiffening, lunging, stalking, growling, snapping)

reliably redirected for inappropriate guardian behaviour (see “resource guarding” below)

Note that “wrong behaviour” is highly contextual, particular in Maremmas but in all dogs. Stiffening, lunging, stalking, growling, or snapping is entirely appropriate when directed at a true threat. That’s where the consistency in YOUR behaviour comes in, so your dog learns the boundaries and when/if to apply its guardian instincts.

Handling problems

A very quick overview and suggestions for managing relatively mild problems.

If you don’t feel you can consistently identify and avoid the triggers for the problematic behaviours your rescue will most likely start exhibiting after 3 weeks, look for professional behaviourists who will guarantee only to use rewards-based training, and who understand livestock guardian dogs.

Identify and avoid

Rescues, having little sense of a calm normal, often learn to escalate behaviours very quickly in order to control a situation that’s out of their control. They may also have little ability to self-regulate emotions and actions.

A situation that non-rescue dog will take in its stride may cause an excessive response in a rescue. For example, a play-chase with another dog may suddenly see the Maremma regard the other dog as a threat and respond accordingly. A happy patting session may suddenly get a snarl.

Your job can often be to identify those triggers, and do everything in your power to completely avoid them in the early stages. There’s plenty of time to work directly on them, when your dog is more relaxed and comfortable.

There are many, many potential triggers, but major ones to be aware of and watch for can include:

Valuable things, such as food, toys, treats, people, or locations. Rescues will often guard these obsessively and escalate into violence to protect “their” valuables. See “Resource guarding” below.

“Choke” points. Many dogs don’t deal with being crowded or feeling they have no escape routes, and will often respond to the feeling with a snap.

Too much unwanted attention. It’s often best to wait for Maremmas to ask for attention, rather than pressing it on them, particularly in the early stages of a rescue’s new life. In particular, limit children’s access to rescue dogs, because children are unpredictable, loud, and can be unobservant of the tiny indicators that a dog is reaching the end of its tether.

Resource guarding

This is common in Maremmas in general, and can be particularly prevalent in dogs that have been missing reliability and consistency in their recent lives.

In short, the Maremma will attach value to something and act to avoid having to share or lose that thing. It can include food, toys, people, other animals, and territory.

It’s extensively covered in a staggering number of books and websites. This is simply a very quick list to start you in the right direction.

Avoidance. Try to learn the main triggers, and then set up ways to completely avoid those triggers. There’s plenty of time to work directly on them, when your dog is more relaxed and comfortable. Avoidance isn’t avoiding the problem; it’s giving yourself time to work on them when the time is right.

Food. If your dog seems prone to guarding food, change food to something delicious that will be eaten immediately, rather than buried or stored for later.

No big chunky bones.

Poultry meat and bones seem to be eaten quickly - up to turkey neck size.

Smaller mammal ribs (lamb, goat, kangaroo, pork) also tend to be eaten quickly.

Any weight-bearing bones are potentially risky, even if cut small. Avoid.

Toys. Remove when not in use, if possible.

Unexpected things. If something random becomes valuable - a particular stick, fallen fruit, a blanket - remove when they’re not looking. If you can’t, try to use “leave it” to swap it out for a high-value food treat and remove entirely.

Territory. It’s ok - to an extent - for rescue dogs to guard the space that you’ve assigned to them, as long as you’re allowed there. For other locations, consider removing or blocking their access to that spot entirely if possible.

You. This is a very tricky one and to be perfectly honest, I haven’t found a foolproof answer yet. Blocking access seems to be the best short-term option, until the time is right for proper counter-conditioning.

Using their fear

Once you have a base level of trust and comfort, you can use that - if and as need be, and only occasionally - to oh-so-gently shape or dissuade the behaviours you do and don't want. You can't use a raised voice or anything that even vaguely resembles violence or aggression, of course, but you can use what they’re really frightened of to dissuade them from things.

I will admit to shamelessly using Bella's fear of my partner to stop her running away, or chasing things I didn't want chased, or move her to a different location, by simply making him stand in her way. That's all - just stand. Not even threateningly. Not even opening his arms and trying to loom. Just being present.

Her fear of him did the rest of the work.

But - and this is important - he didn't actually do anything to make the fear worse.

When he wants to be non-threatening, he sits down and talks nonsense to her. Simply by sitting down, he changes from “scary” to “comforting”, and she comes straight over for a pat.

Now that's she's broadly overcome her fear of him - and she has put in as much into overcoming the fear as she has (I've never seen a dog consciously fight to override her own instincts like I've watched Bella do it. I'm in awe) - I can't really use that any more. Dammit

(On the other hand, I don't NEED to ... ).

So you can do similar, if you need to.

Use standard dog training

Standard positive reinforcement dog training methods should work, depending on age, and adjusting for Maremma requirements.

Concentrate on the very basics first; the ones that give you a measure of control. These are not “tricks”; they are the very basis of having suitable control over your dog in any likely situation.

These include:

Sit. Ideally with appropriate hand movements. A sitting dog can’t lunge, jump, or run away.

Down. Like sit, but with even more control.

Wait or Stay. Best in conjunction with Sit or Down.

Leave it or Give me. This can be a big iffy with rescue dogs but if you can get even the vague concept across, can help a lot with resource guarding.

See “greet with joy” above for a method that somewhat accidentally gets you a sort of recall. It may work where a more standard recall training method may not work.

And finally …

Take it really, really slowly. Generally, they will improve, but you're looking at months and years, not hours or days.

There will be times when your dog seems to go backwards. This is normal and expected; don't get disheartened. Learning to recover from setbacks is, in fact, part of the healing/trust/re-learning process, and is valuable for both of you.

A few places to find more information

Books

These three books are aimed at positive dog training in general, with a specific focus on rescue dogs. They are not targetted to Maremmas and some sections may need adjusting to cater to known Maremma behaviour - for eg, around barking or guarding.

I have, however, found them very helpful.

The Dog Trainer's Complete Guide to a Happy, Well-Behaved Pet: Learn the Seven Skills Every Dog Should Have. By: Jolanta Benal.

Do Over Dogs - Give Your Dog A Second Chance for A First Class Life (Dogwise Training Manual). By: Pat Miller

Mine! - A Practical Guide To Resource Guarding In Dogs. By: Jean Donaldson

Social media

Maremma (Maremmano Abruzzese) Australia. Particularly the Files section. This group taught me so much, and saved my sanity when I thought I was doing everything wrong.

Training Support for Livestock Guardian Dogs. In particular, their superb Guides.

Australian Maremma/LGD rescue organisations

If you approach these people nicely, they are generally very generous with support and suggestions, as they’ve been handling Maremmas with problem behaviours for longer than I’ve been writing.

General: Livestock Guardian Dog Rescue in Australia (Facebook)

NSW: Companions For Life Pet Rescue (website), Maremma Sheepdog's in Rescue Australia/ Companions for Life (Facebook)

NSW: Kindly Animal Sanctuary (website), Kindly Animal Sanctuary (Facebook)

Qld: Fresh Start Rescue Incorporated (website), Fresh Start Rescue Incorporated (Facebook)

Vic: Maremma Rescue Victoria (website), Maremma Rescue Victoria (Facebook)

WA: West Coast Maremma Rescue (website), West Coast Maremma Rescue (Facebook)

Websites

www.maremmano.com: The world’s most comprehensive web site for the Maremma Sheepdog. AND it’s Australian :)

Got a story to tell about your rescue dogs? More tips and tricks and things that have worked for you? Tell me in the comments!